Mauna Kea has long been a place for spiritual ceremonies. It is Hawaii's most sacred mountain. Here on this web site you can see documentation of the involvement of contemporary Hawaiians who have been reintroducing the Hawaiian culture on top of their Temple during the first decade of the Third Millennium.

Mauna Kea has long been a place for spiritual ceremonies. It is Hawaii's most sacred mountain. Here on this web site you can see documentation of the involvement of contemporary Hawaiians who have been reintroducing the Hawaiian culture on top of their Temple during the first decade of the Third Millennium.

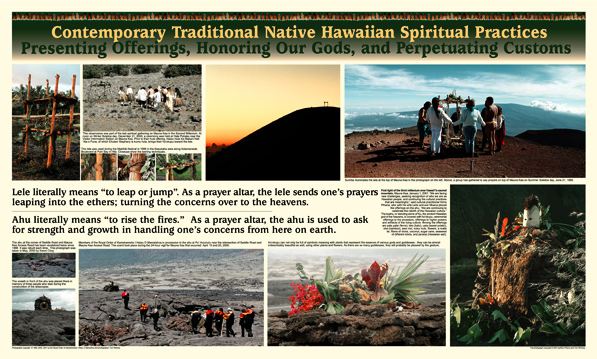

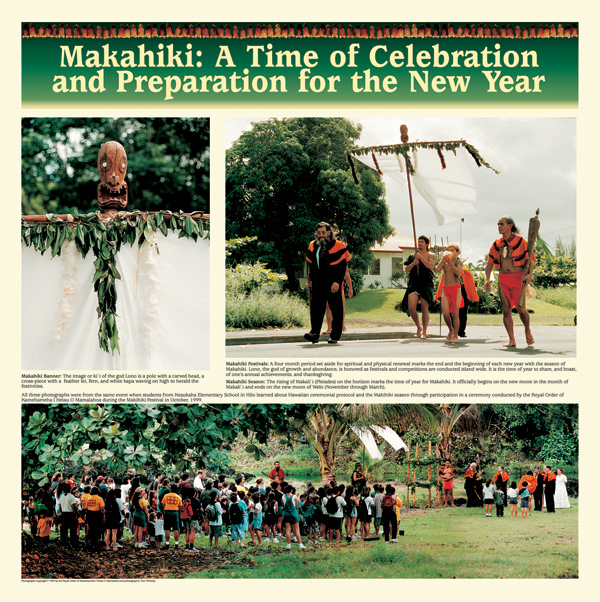

miIt also presents the exhibition that has appeared in three Hawaii museums, the Lyman Museum in Hilo in 2001, the Bishop Museum in Honolulu in 2003 and the Pahoa Museum in Pahoa in 2009. After the exhibition in Pahoa, most of the panels were destroyed in a flash flood. We have been told that students have found that photographs and words about the culture in the exhibition and now found on this site have helped them get good marks on school projects so the permanent home of the exhibition is now here on the Internet.

miSponsors of the exhibition include the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, Mauna Kea Anaina Hou, the Kanakamaoli Religious Institute, and the Maka‘ainanaFoundation. Individuals who assisted are listed lower in the column on the left.

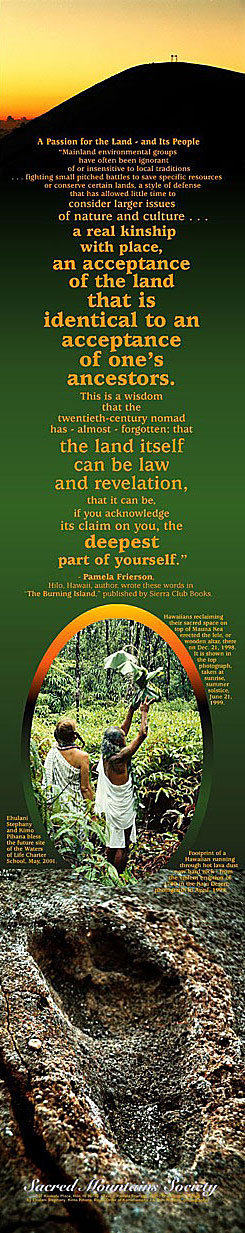

miThe photograph at the top shows Hawaiian cultural warrior Keoni Choy standing watch after ho‘okupu, or offerings to the ancestors, were placed on the lele (altar) on the highest part of Mauna Kea on winter solstice day, December 21, 1999. It is freezing cold and he is standing there in his malo! This highest point was named Kukahau‘ula by ancient Hawaiians, honoring the god Ku. The summit is now called Pu‘u Wekiu. In the lower set of photographs, Harold Kaula is on the left and on the right is Calvin Kaleiwahea. In the center is the most recent poster that was used to announce the exhibition. Dominic Vea is holding a ho‘okupu with Mauna Kea in the background. A young Devin Pihana is blowing the pu or chonch shell in the photograph in the left column. He can be seen in a lower panel with a group announcing the opening of the Makihiki in Hilo. At the bottom is a spectacular sunrise visible through a slit in the clouds on the Autumnal Equinox, September 21, 2001. On the left in the yellow wrap is Koa Ell, carrying an offering to the lele in the area beyond the parking lot at the Onizuka Visitors Center on Mauna Kea.

The text on these panels that appeared in the museum exhibition is reproduced below each panel.

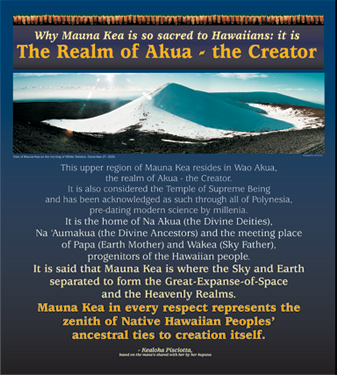

Onipa‘a Mauna Kea a Wakea “I am a native Hawaiian. I have a right to practice my religion in the environment of my belief.” – Kealoha Pisciotta at a public hearing on the University of Hawai‘i’s Mauna Kea Master Plan, 1998.

Pisciotta is a former employee of the James Clerk Maxwell Sub-Millimeter Radio Telescope who repeated the statement above in front of thirty to forty witnesses while attempting to reclaim her family shrine (shown on the lower left, above) from a University of Hawai‘i employee in the parking lot of the Hale Pohaku Visitor Information Center on Mauna Kea.

The shrine, a two-foot-high pohaku (stone), had been moved once before, when it had been taken to the County dump in Hilo where by chance she found it and replaced it on the mountain.

So when it had been moved again and found in the University employee’s truck, she was irritated. The man at first refused to return the pohaku. She kept repeating her statement of rights until he finally threw the stone into her van. In late 1998 it was taken a third time and has never been recovered.

The University of Hawai‘i Institute for Astronomy has since formally apologized to Kealoha for these actions.

It was with a cry of frustration that Kealoha told her story to a group of Hawaiian activists one evening shortly after the 1998 incident. The group had met to discuss the continued desecration of Mauna kea. It was clear to those present at the meeting that there had been enough interference with the fundamental rights of kanakamaoli (Hawaiians) to worship on Mauna Kea, their temple.

There was also strong concern that forty years of telescope building had evidenced little attention to the concerns of Native Hawaiians regarding the cultural and spiritual history of the mountain, as was documented in the State Auditor’s report in 1999.

The worship that occurs on Mauna Kea has occurred for thousands of years and has been mostly conducted in private. However, these recent events and much discussion led to a plan, “Onipa‘a Mauna Kea a Wakea,” meaning “stand fast and resist the affront to the Sacred Temple – Mauna Kea,” that was formed to reassert the right to continue to worship.

The leadership skills of Kaliko Kanaele, Kahu o Te Rangi and Kimo Pihana as members of Aloha ‘Aina were called upon as the group agreed on an effort to erect a Hawaiian altar on the very top of the mountain and focus ceremonies around it.

Winter Solstice day on December 21, 1998, was deemed an auspicious time for the first public ceremony. A Hawaiian lele (a wooden altar) was assembled at Pu‘u Huluhulu the day before. Skippy Keli‘i Ioane demonstrated traditional methods to tie and fit the lele to withstand the harsh conditions on the summit.

At sunrise the lele was carried by members of Aloha ‘Aina and Mauna Kea Anaina Hou from the parking area near the University of Hawai‘i telescope down and across and up to the very top of Pu‘u Kukahau‘ula (the ancient name for the summit now known as Pu‘u Wekieu) at the elevation of 13, 796 feet as shown in the photograph on the left.

Powerful prayers were laid across the panoramic vista visible from the lele that was then secured “on top of the world.” This historic ceremony was witnessed and blessed by Ali‘i Nui Arthur Mahi of Nakoa o Hawai‘i, who was dressed in a malo and chiefly cape.

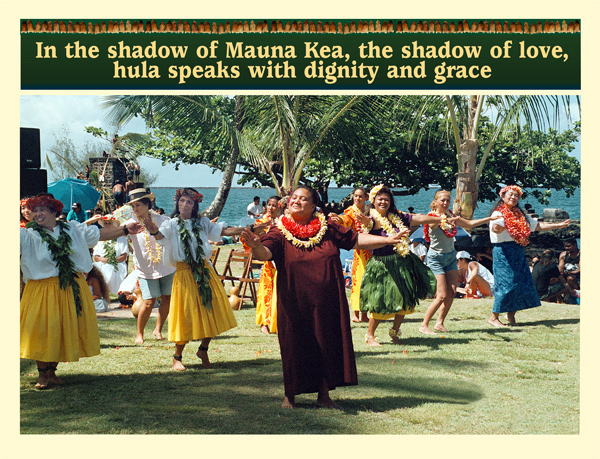

Kumu Hula Pua Kanakaole Kanahele and her hula halau gathered later at Pu‘u Huluhulu to lead a ceremony with members of the Hilo and Waimea Civic Clubs and other participants from the community. Aunty Pua made an impassioned statement calling for an end to telescope expansion on the mountain and further desecration of sacred Mauna Kea.

On Summer Solstice June 21, 1999, a more accessible lele (shown above) was erected at the 9,000-foot elevation in the open field behind the Onizuka Visitor Information Station. This lele was erected by the same parties, but now they performed the task as Chiefs of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I Heiau o Mamalahoa. The raising of the lele was officially blessed by Ali‘i Aimoku Gabriel Makuakane, Moku o Kona.

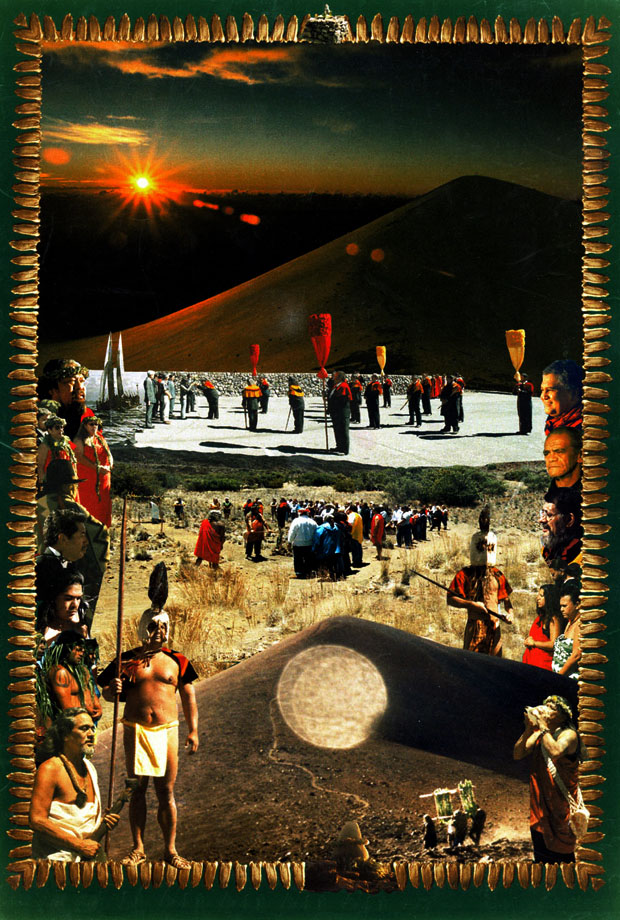

Princess Sayako of Japan arrived in Hawai‘i on September 17, 1999, to attend the blessing and dedication of the Subaru Telescope on top of Mauna Kea. The Royal Order of Kamehameha I, by invitation of Pukaua Nui Ali‘i Wally Lau through the Japanese Consulate, officially greeted Her Highness on the sacred mountain.

It was a thrilling moment for the Royal Order people as Kaliko Kanalele held the ho‘okupu with Princess

Sayako of Japan with Secret Service people and ambassadors and protocol officers in attendance, as

described in more detail and shown in the bigger photograph on the Royal Order's panel below.

A ceremonial stone altar or ahu was built on December 31, 1999, at Pu‘u Huluhulu near the Saddle Road and Mauna Kea Access Road intersection by Kimo Pihana, Harold Kaula and Keoni Choy.

On the left is the stone ahu altar that was constructed on the grounds of the ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu by Hawaiian Culture Activists. In the middle is the ahu erected at Pu‘uhuluhulu in 1999. On the right, the photograph show the desecration of that ahu after it was smashed by unknown people. It was rebuilt by Pihana, Kaula and Choy. On New Year's Eve of 1999 the Pihana ‘Ohana placed ho‘okupu offerings on the new ahu to be ready with prayers in a glorious manner on Mauna Kea at the dawn of the Third Millennium in Hawai‘i, shown below in the panel explaining ahu and lele in more detail.

mOn April 18 and 19, 2000, a 24-hour vigil was conducted at the new ahu to seek protection of

Mauna Kea from further construction or development, and to urge that it be fully recognized and honored properly as a sacred mountain. This ceremony was sanctioned by the Royal Order of Kamehameha I and witnessed by Ali‘ Aimoku Paul Neves, Lani Ali‘i Ernest Akoni of Heiau o Mamalahoa and Ali‘i Aimoku Wayne Iokepa, Moku o Kona.

Mauna Kea from further construction or development, and to urge that it be fully recognized and honored properly as a sacred mountain. This ceremony was sanctioned by the Royal Order of Kamehameha I and witnessed by Ali‘ Aimoku Paul Neves, Lani Ali‘i Ernest Akoni of Heiau o Mamalahoa and Ali‘i Aimoku Wayne Iokepa, Moku o Kona.

Three altars on three levels had been secured by the Chiefs for ceremonial worship by all who come to the sacred mountain of Mauna Kea.

Kaliko Kanaele and Jonathan Naone stand watch and Ninea Parks and Toni

Yardley stay warm during the 24-hour vigil for Mauna Kea

Recent history of ceremonies

Public ceremonies have regularly been conducted at the top of Mauna Kea on Equinox and Solstice days since the altars were placed on the mountain. Many ohana (families) and other small groups and individuals regulates visit the mountain for private spiritual observance.

Summer solstice ceremony at the wooden lele altar located in the area beyond the parking lot at the Onizuka Visitor Information Center on Mauna Kea that occurred in 2001.

Summer solstice ceremony at the wooden lele altar located in the area beyond the parking lot at the Onizuka Visitor Information Center on Mauna Kea that occurred in 2001.

These people participated in an Autumnal Equinox ceremony , September 21, 2003.

These people participated in an Autumnal Equinox ceremony , September 21, 2003.

These two photographs show ceremonies on top of Mauna Kea conducted at Winter Solstice in 2006.

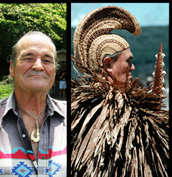

Here four people on December 20, 2009, and have buried ho‘okupu and sent his essence outward and upward as the freezing winds and snow blow across the summit to honor Willie Grey Eagle, a Native American who came to Hawai‘i decades ago and mastered the little known craft of making mahioli, the elaborate helmets ancient Hawaiian royalty and ail‘i wore. Mahioli created by Grey Eagle are worn by many Hawaiian cultural activists today, as shown here. He shared this esoteric skill, his good humor and his advocacy of reviving the use of olona, an uncommonly strong fiber that was cultivated by ancient Hawaiians for use in making capes and strong cordage for canoes and ships. He was a gentle and good man who was extremely supportive of the Hawaiian culture who will be missed by all who knew him. It was said he died happy.

Here four people on December 20, 2009, and have buried ho‘okupu and sent his essence outward and upward as the freezing winds and snow blow across the summit to honor Willie Grey Eagle, a Native American who came to Hawai‘i decades ago and mastered the little known craft of making mahioli, the elaborate helmets ancient Hawaiian royalty and ail‘i wore. Mahioli created by Grey Eagle are worn by many Hawaiian cultural activists today, as shown here. He shared this esoteric skill, his good humor and his advocacy of reviving the use of olona, an uncommonly strong fiber that was cultivated by ancient Hawaiians for use in making capes and strong cordage for canoes and ships. He was a gentle and good man who was extremely supportive of the Hawaiian culture who will be missed by all who knew him. It was said he died happy.

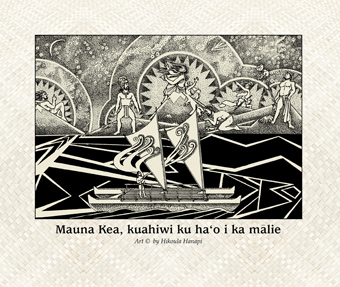

Cultural history extensive

The cultural history of the mountain is extensive. Kepa Malay, in a study done for expanding the scope of astronomy facilities on the mountain found that “Mauna kea has been the focal point of numerous traditional and historical Hawaiian practices and narratives recorded by both Hawaiian and foreign visitors; and Mauna Kea is the home of many traditional Hawaiian sites, temporary residences, burials, trails, ko‘i (adz) quarry complexes and other cultural and natural resources that are of both traditional and contemporary importance to the Hawaiian people.” Malay documented this in “Mauna Kea – Kuahiwi, Ku Ha‘o I Ka Malie,” a report on archival historical and documentary research by Kumu Pono Associates in 1997.

Mauna Kea is honored by many cultures

There are many sacred mountains in the world. Mauna Kea is the tallest and most sacred mountain in the Polynesian Triangle, is mentioned in Hawaiian and Polynesian oral history, and may play a role in the spiritual traditions of other people. When Kimo Pihana was a Ranger on Mauna Kea he talked with people from many cultures who asked about the mountain and said prayers on Mauna Kea, including Tahitians, Samoans, Marquesans, Russians, Japanese, Tibetans, Cloud People from Oaxaca, Mexico, Maori and many other cultures. See the panel related to the Navajo people at the bottom of this web page.

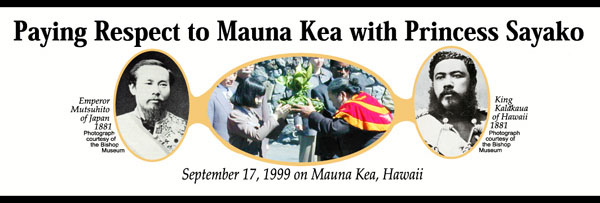

In the middle photograph above, Princess Sayako of Japan meets with members of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I which represents the protocol of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Princess is acknowledging a ho’okupu (offering) presented by Mamo Kaliko Kanele, Sr., that was later placed on an lele (altar) at the top of Mauna Kea top honor the ancestors. She was here in Hawai‘i to dedicate the Subaru telescope on top of Mauna Kea, one of eleven telescopes sponsored by thirteen nations on top of Mauna Kea. Witnessing the ceremony in the group behind the Princess were former U. S. Ambassador to Japan Thomas Foley, former Prime Minister of Japan Toshiki Kaifu and General Consul of Japan Gotaro Ogawa.

This formal ceremony with Princess Sayako echoes the historic meeting between the Emperor Mutsuhito of Mejii Japan and King Kalakaua of Hawai‘i in Tokyo in 1881 as the King was pursuing diplomatic initiatives to encourage immigration of Pacific Island people to Hawai‘i during his trip around the world. At the time, King Kalakaua bestowed the title of Knights Grand Cross with Collar as he was made a member of the Royal Order.

The Royal Order’s Ali’i Aimoku Sir Paul K. Neves commented on the event: “ ‘The inherent sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness,’ was proclaimed by King Kamehameha III upon restoration of the Hawaiian government, July 31, 1843. We, the Royal Order of Kamehameha I and our supporters, remain mindful of our responsibility under Kingdom Law to the people, to hold sacred our Mauna Kea.”

“We did express our sincere concern with regard to its use and development with Her Imperial Highness Princess Sayako,” said Neves. “Also mindful of our ancient culture and our own ancient astronomers, we encourage our people as well as all people of good will to continue to discuss concerns with regard to the care of Mauna Kea so that the sacred mountain continues to be beneficial to all humanity.”

Many wahine were in attendance and proudly paid their respects to the Princess, as well.

Ali`i Nui Herman Kanae (center left) joins Ali`i Ai Moku Paul Neves (in dark glases) with his chiefs and supporters at the summit of Mauna Kea for Winter Solstice ceremony 2002.

Ali`i Nui Herman Kanae (center left) joins Ali`i Ai Moku Paul Neves (in dark glases) with his chiefs and supporters at the summit of Mauna Kea for Winter Solstice ceremony 2002.

The sunrise photograph above shows a 2004 ceremony on top of Mauna Kea. The same lele is shown in the middle photograph in the lower panel. On the left below we wanted to show the different types of lele that are in use in Hawai‘i. It shows a three-leg lele used in a blessing ceremony for a landowner in Hawaiian Paradise Park. On the right the photograph shows Hank Fergerstrom placing ho‘okupu on the lele located beyond the parking area at the Onizuka Visitor Information Station on Mauna Kea.

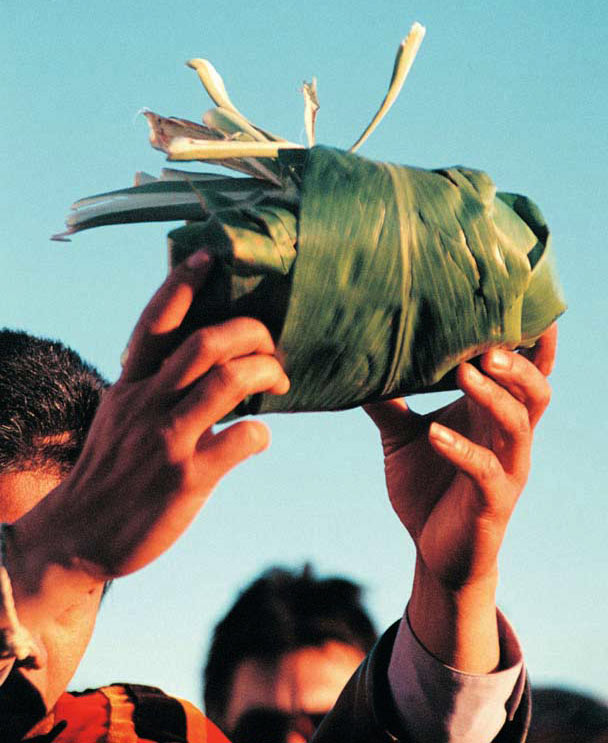

Here Dominic Vea proffers a ho‘okupu, and offering, that will be placed on the wooden lele altar

on the top of Mauna Kea. The beautiful photograph was taken by Gladys Suzuki and used with her permission.

Ho‘okupu was given an excellent discussion by Ka'iana Haili and is used here with permission from this website (http://www.hawaii.hawaii.edu/hawaiian/KHaili/hookupu.htm): "Ho`okupu is a physical contribution of an individual or group request for acknowledgement from a specific deity or source. Ho`okupu is used to ensure growth, increase mana, literally: to cause to sprout. Your ho`okupu could be your voice [oli], a kinolau [physical manifestation of deity i.e. awa, kalo, i`a] or something that is made by or precious to the individual or group making the request.

"A ho`okupu is an offering of symbolic significance for the occasion. It may be a certain type of food or plant, a song or chant, perhaps even a rock or water from your homeland. Sometimes the item is dictated by the particular ceremony, other times, by what the individual feels is appropriate. In offering the ho`okupu, as the word indicates, one asks for growth; that one’s request be granted; that there be a reciprocation; that there be an exchange of mana or life force.

"Ho`okupu is a traditional protocol among the Kanaka Maoli `O Hawai’i [indigenous people of Hawai`i] that is dictated by hö`ihi [respect] for the host, land, ancestors or gods. It establishes a connection between the giver and the receiver that is culturally appropriate.

"Literally: ‘to cause to sprout’ is a literal definition – ho`o = in causative /simulative for – kupu = sprout, growth.”

Ka‘iana Haili teaches at Hawai'i Community College in Hilo, an excellent place to learn more about the Hawaiian culture.

Remember, to read the tiny type on these panels, you can easily open the PDF files for any of the panels

by clicking on the panels themselves and the PDF file for that panel will open.

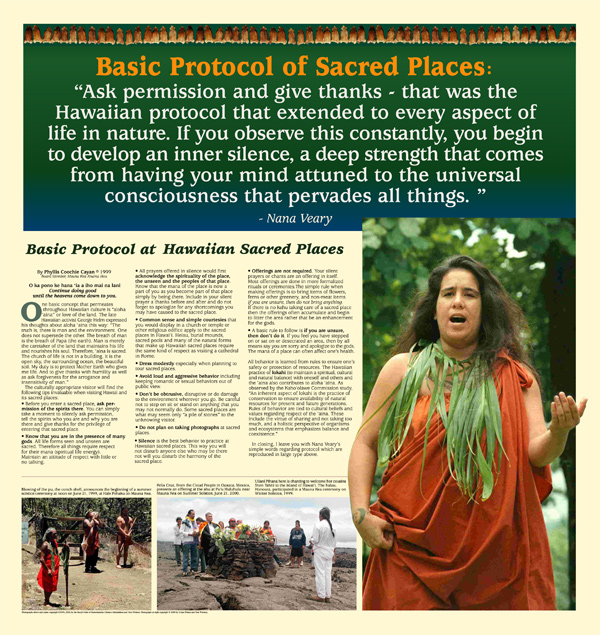

Basic Protocol at Hawaiian Sacred Places By Phyllis Coochie Cayan © 1999

Board Member, Mauna Kea Anaina Hou

One basic concept that permeates throughout Hawaiian culture is “aloha ‘aina” or love of the land. The late Hawaiian activist George helm expressed his thoughts about aloha ‘aina this way: “The truth is, there is man and the environment. One does not supersede the other. The breath of man is the breath of Papa (the earth). Man in merely the caretaker of the land that maintains his life and nourishes his soul. Therefore, ‘aina is sacred. The church of life is not a building; it is the open sky, the surrounding ocean, the beautiful soil. My duty is to protect Mother Earth who gives me life. And to give thanks with humility as well as ask forgiveness for the arrogance and insensitivity of man.”

The culturally appropriate visitor will find the following tips invaluable when visiting Hawaii and its sacred places.

• Before you enter a sacred place, ask permission of the spirits there. You can simply take a moment to silently ask permission, tell the spirits who you are and why you are there and give thanks for the privilege of entering that sacred place.

• Know that you are in the presence of many gods. All life forms seen and unseen are sacred. Therefore, all things require respect for their mana (spiritual life energy). Maintain an attitude of respect with little or no talking.

• All prayers offered in silence would first acknowledge the spirituality of the place, the unseen and the peoples of that place. Know that the mana of the place is now a part of you as you become part of that place simply by being there. Include in your silent prayer a thanks before and after and do not forget to apologize for any shortcomings you may have caused to the sacred place.

• Common sense and simple courtesies that you would display in a church or temple or other religious edifice apply to the sacred places in Hawai‘i. Heiau, burial mounds, sacred pools and many of the natural forms that make up Hawaiian sacred places require the same kind of respect as visiting a cathedral in Rome.

• Dress modestly especially when planning to tour sacred places.

• Avoid loud and aggressive behavior including keeping romantic and sexual behaviors out of public view.

• Don’t be obtrusive, disruptive or do damage to the environment wherever you go. Be careful not to step on, sit or stand on anything that you may not normally do. Some sacred places are what may seem only “a pile of stones” to the unknowing visitor.

• Do not plan on taking photographs at sacred places.

• Silence is the best behavior at practice at Hawaiian sacred places. This way you will not disturb anyone else who may be there nor will you disturb the harmony of the sacred place.

• Offerings are not required. Your silent prayers or chants are an offering in itself. Most offerings are done in more formalized rituals or ceremonies. The simple rule when making offerings is to bring items of flowers, ferns or other greenery, and non-meat items. If you are unsure, then do not bring anything. If there is no kahu taking care of a sacred place then the offerings often accumulate and begin to litter the area rather than be an enhancement for the gods.

• A basic rule to follow is, if you are unsure, don’t do it. If you feel you have stepped on or say on or desecrated an area, then by all means say you are sorry and apologize to the gods. The mana of a place can often affect one’s health.

All behavior is learned from rules to ensure one’s safety and the protection of resources. The Hawaiian practice of Lokahi (to maintain a spiritual, cultural and natural balance) with oneself and others and the ‘aina also contributes to aloha ‘aina. As observed by the Kaho‘olawe Commission study, “An inherent aspect of Lokahi is the practice of conservation to ensure availability of natural resources for present and future generations. Rules of behavior are tied to cultural beliefs and values regarding respect of the ‘aina. These include the virtue of sharing and not taking too much, and a holistic perspective of organisms and ecosystems that emphasizes balance and coexistence.” In closing I leave you with Nana Veary’s simple words regarding protocol which are reproduced in large type on the poster shown above: "Ask permission and give thanks - that was the Hawaiian protocol that extended to every aspect of life in nature. If you observe this constantly, you begin to observe an inner silence, a deep strength that comes from having your mind attuned to the universal consciousness that pervades all things."

h

h  Heros of the Sea By Leila Pihana These drawings have been a turning point for me. I awoke one evening and realized that I had been dreaming to recall the past and look to the future. I looked into the sky and there was Hokule‘a shining. I could not go to sleep after that. My heart was filled with the joy of seeing my ancestors.

Heros of the Sea By Leila Pihana These drawings have been a turning point for me. I awoke one evening and realized that I had been dreaming to recall the past and look to the future. I looked into the sky and there was Hokule‘a shining. I could not go to sleep after that. My heart was filled with the joy of seeing my ancestors.

My drawings honor all of the many generations before me; tell the story of their courage and spirit in searching for a new birth land for the generations to follow; and tell how they found this new place, guided in canoes by the stars and finally by sight of the mighty peak of Mauna Kea. They found a new land that became a home to people of many races.

Cultural historians tell us that long ago, way before Captain James Cook first set eyes on Hawai‘i, that many dark-skinned sea farers from both the Marquesas and the Society islands had sailed here in their double-hulled canoes. Evidence also indicates that these early voyages were not accidental. Once the new land was discovered, navigators worked out sailing directions for it. Guidance was provided be a compass derived from the rising places of stars on the Eastern horizon, their setting places on the Western horizon and the constant direction of the dominant ocean swells. It was about 1,500 years ago that the first South Pacific islanders discovered Hawai‘i and made it their home. – © Leila Pihana, Hilo, Hawai‘i, 1.12.2001

Remember, to read the tiny type on these panels, you can easily open the PDF files for any of the panels by clicking on the panels themselves and the PDF file for that panel will open.

m

m Mauna Kea is a beacon for navigators Grandmaster Navigator Pius Mau Piailug, from the island of Satawal, Micronesia, was warmly welcomed and honored on the Big Island of Hawai‘i on Sunday morning, June 24, 2001. Mau, 76, was instrumental in helping Hawaiians for the past 27 years to relearn the art of traditional navigation. In a triumph for the thousands of people who have been involved in the revival of the art of navigation, the Hokulea in the photograph above on the left is shown leaving Hilo on the final leg of its sea voyage to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The effort completed Hawaiian voyaging canoes’ circuit of the entire Polynesian Triangle and the connection to Micronesia. Navigators used traditional methods of finding their way guided by the stars. Those methods predate the modern science of astronomy by thousands of years.

Mauna Kea is a beacon for navigators Grandmaster Navigator Pius Mau Piailug, from the island of Satawal, Micronesia, was warmly welcomed and honored on the Big Island of Hawai‘i on Sunday morning, June 24, 2001. Mau, 76, was instrumental in helping Hawaiians for the past 27 years to relearn the art of traditional navigation. In a triumph for the thousands of people who have been involved in the revival of the art of navigation, the Hokulea in the photograph above on the left is shown leaving Hilo on the final leg of its sea voyage to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The effort completed Hawaiian voyaging canoes’ circuit of the entire Polynesian Triangle and the connection to Micronesia. Navigators used traditional methods of finding their way guided by the stars. Those methods predate the modern science of astronomy by thousands of years.

Hawai‘i Island’s voyaging canoe Makali‘i, in the photograph across the bottom of the panel, sailed Master Navigator Mau Piailug home to Satawal.

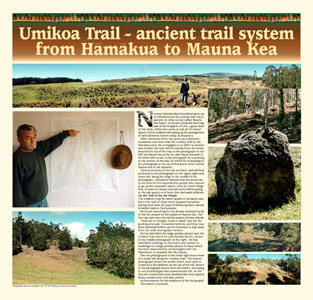

Umikoa Trail Norman Kalejola’akea Gonsalves grew up in Hamakua and as a young man was a paniolo on what is now called Mauna Kea Ranch. In ancient times, the land was part of the kingdom of Umi, a great chief of the early 1600s who came to rule all of Hawai‘I Island. Umi is credited with setting up the arrangement of land divisions known today as ahupua‘a.

After retirement from his career as a detective, Gonsalves now lives near the Umikoa Trail in the Hamakua area. He is engaged in an effort to protect and reclaim the trail that extends from the ocean up Mauna Kea as far as Lake Weiau. In the photograph, he is pointing to the section of the trail on which he is standing in the photograph at the top of the panel that shows Mauna Kea in the distance.

Various sections of the trail are fairly well defined as shown in the photograph on the upper right and lower left, along the ridge in the middle of the photograph. Gonsalves believes that the protocols of the time of Umi required that people who wanted to go up the mountain had to come to Umi’s village first, to leave ho‘okupu and talk story before going to the adz quarry or to bury their deceased relatives.

On the trail of the Mu people

The evidence may be rather sparse in his latest case, but a think trail of clues never stopped Gonsalves during more than forty years of following faint, almost invisible trails to find answers.

He is now searching for the almost-vanished traces of the Mu people on the slopes of Mauna Kea. The Mu may have been the earliest settlers of these islands.

“Hurt not in thought, word or deed,” was the Mu guiding principle, Gonsalves believes. He thinks they may have retreated further up the mountain to stay away from the strife among later settlers.

He has identified the large pohaku (stone) near the Umikoa Trail that he calls Pohaku Na Mu, shown in the middle photograph on the right. He has identified markings on the stone that are very similar to markings on a large stone in Maui, which has been associated by archeologists with the Menehune, or possibly the Mu culture.

The two photographs on the lower right show (in the panel above, right) views of a small hill along the Umikoa Trail. The bottom photograph shows the stones that were used to construct a flat platform on the top of the hill, shown in the photograph second from the bottom. According to one archeologist who examined the hill, he felt that the construction style predated the more typical Heiau construction of a later period.

Is this evidence for the existence of the MU people?

The search continues.

mm

mm

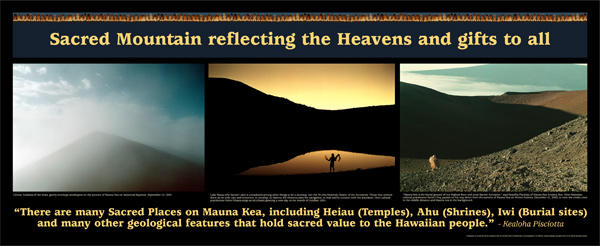

Panoramic photograph at the top shows an unusual slit in the clouds at sunrise at Autumnal Equinox, September 22, 2001; middle left shows the shadow of Mauna Kea viewed toward the west at sunrise on the Autumnal Equinox, September 22. 2001; sun in the middle taken at Summer Solstice, June 21, 2000; middle right photograph taken by Gladys Suzuki at Winter Solstice, December 21, 2000. At the bottom is a composite of photographs taken by Tom Whitney to comprise the panorama of the sunrise of the Summer Solstice, June 21, 1999.

Panoramic photograph at the top shows an unusual slit in the clouds at sunrise at Autumnal Equinox, September 22, 2001; middle left shows the shadow of Mauna Kea viewed toward the west at sunrise on the Autumnal Equinox, September 22. 2001; sun in the middle taken at Summer Solstice, June 21, 2000; middle right photograph taken by Gladys Suzuki at Winter Solstice, December 21, 2000. At the bottom is a composite of photographs taken by Tom Whitney to comprise the panorama of the sunrise of the Summer Solstice, June 21, 1999.

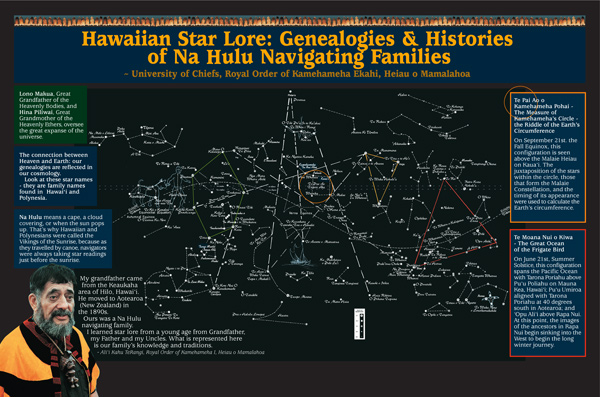

We see our family's genealogy in the stars. My grandfather came from the Keaukaha area of Hilo, Hawai‘i. He moved to Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the 1890s. Ours was a Na Hulu navigating family. I learned star lore from a young age from Grandfather, my Father and my Uncles. What is represented here is our family’s knowledge and traditions. - Ali‘i Kahu TeRangi, Royal Order of Kamehameha I, Heiau o Mamalahoa

First Rainbow on Mauna Kea

Contemporary Japanese Oshi-e (fabric assemblage)

By Wendy Christine Duke

Wendy's website is http://www.cloudhavenstudio.com/

Inspiration In the short time that I lived in Hawai’i, I had many opportunities to drive to the summit of Mauna Kea. It was always an awe-inspiring experience. My trip to celebrate the Autumnal Equinox in 2001 was the best and it inspired this artwork. To prepare for this special event, my husband Lee and I intended to make a traditional ho’okupu to bring as an offering.

As he was going around the garden gathering the eleven ti leaves, I was “told” to have him pick a “rainbow of flowers” to place inside the ti leaf bundle, starting and ending with small white orchids. Even though this was not what we had intended to do, nor what we were taught to do, I always listen when Spirit talks to me, so the Rainbow Ho’okupu was created.

As we drove into Hilo that evening to begin the ceremonies, Lee asked me to “look” and see what the weather would be like at the summit for sunrise. I heard an odd thing - that we would be “enshrouded.” No other information was given! Puzzling over what this meant, we arrived at the meeting hall of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I Heiau o Mamalahoa on Kalanianaole Boulevard at Puhi Bay in Hilo to join many of their members and 25 other celebrants for about twelve hours of sharing food, stories and ceremonies, culminating with the sunrise chants and walk to the summit.

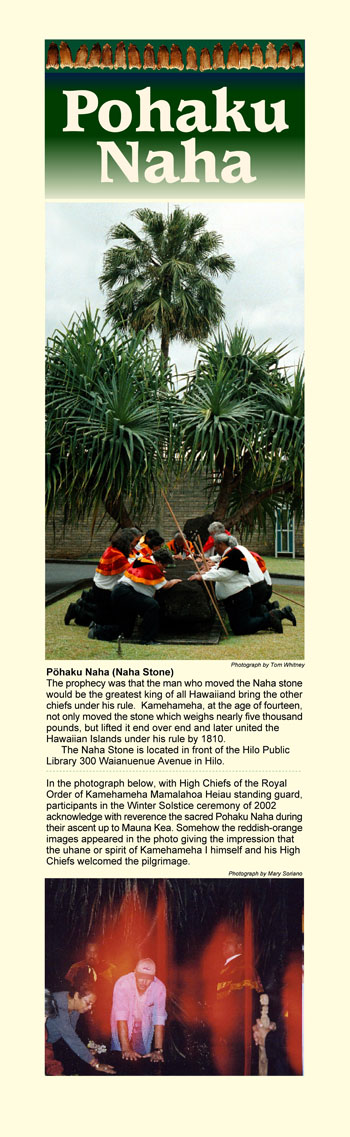

Around midnight, we made our way in a procession of cars, gathering first at the Naha stone in front of the Public Library on Waianuenue Avenue in Hilo. Then we drove up Saddle Road to Pu’u Huluhulu for more ceremony, and finally up to the 9,300’ level at the Visitor Information Station to acclimate and try to sleep before the last leg of the journey.

Just before dawn we went to the summit, parking our cars around the observatories and gathering (or should I say huddling) in the pre-dawn chill facing East, with the actual summit just to our right. Stars were disappearing, and the light of day coming was our only warmth.

There is nothing I can think of that is more amazing than listening to and joining in the chant as we welcomed the sun on the first clear and beautiful day of fall.

When the chants were complete and the sun had risen, I decided to join about ten other hearty souls who wanted to go with the two members of the Royal Order and climb to the actual summit. Dressed in the warmest clothing I had, I nestled my rainbow offering inside my serape, held onto my walking stick for dear life, and, following the drumbeat created by the younger hikers behind me, made my way slowly down and then up the frost-slick cinder slopes of Mauna Kea.

The ceremonies and protocol at the summit were beautifully and creatively done, incorporating the beliefs and wishes of all participants. Each offering was individually blessed and placed on the lele, after which we sat in a circle and shared what we needed to say and do to complete our experience. We must have spent nearly an hour on the top, and although we were each numb with cold, no one wanted the experience to end.

Just as we had completed our ceremony, a white mist totally encircled us, blocking our view of the rest of the world, leaving us alone on the summit enshrouded! It was as if we became an island unto ourselves. The photograph below shows this mist, from a vantage point back by the observatories.

As some of the younger participants began to walk back down into the mist, the best and most amazing thing happened. There were four of us remaining on top, and we looked up, and there, in the mist, was a perfect high arch... a WHITE rainbow!!! We hooped and hollered and sang praises and felt VERY blessed. It was then I remembered the offering I brought, our funny little rainbow ho’okupu! What an affirmation!! I smiled all the way back.

Who knows? Maybe the First Day had a rainbow just like ours - here at the place where, according to Hawaiian legend, all Life began.

"Mauna Kea, Snow, 1999," a painting by Dominic Tidmarsh, a Hawai‘i artist who has long had a fascination with the mountain.

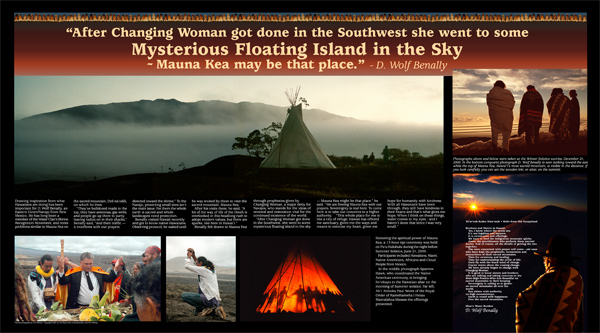

Drawing inspiration from what Hawaiians have been doing has been important for D. Wolf Benally, an Eastern Dineh/Navajo from New Mexico. He has long been a member of the Water Clan’s Shrine Recognition Movement, and notes problems similar to Mauna Kea on the sacred mountain, Dzil Na’odili on which he lives in New Mexico.

Drawing inspiration from what Hawaiians have been doing has been important for D. Wolf Benally, an Eastern Dineh/Navajo from New Mexico. He has long been a member of the Water Clan’s Shrine Recognition Movement, and notes problems similar to Mauna Kea on the sacred mountain, Dzil Na’odili on which he lives in New Mexico.

“They’ve bulldozed roads to the top, they have antennas, gas wells and people go up there to party leaving radios on in their shacks,” Benally said, “And their traffic – it interferes with our prayers directed toward the shrine.” To the Navajo, protecting small sites is not the main issue. For them the whole earth is sacred and whole landscapes need protection - a point that Hawaiians are making about Mauna Kea.

Benally visited Hawai‘i recently and got to know Native Hawaiians. Observing protocol, he waited until he was invited by them to visit the sacred mountain, Mauna Kea.

After his visits there, he said, “A lot of the way of life of the Dineh is overlooked in this headlong rush to adopt modern values, but there are sparks, like here in Hawai‘i.”

Benally felt drawn to Mauna Kea through prophesies given by Changing Woman, a major deity for the Navajos, who stands for the ideas of renewal and restoration vital for the continued existence of the world.

“After Changing Woman got done in the Southwest, she went to some mysterious floating island in the sky – Mauna kea might be that place,” he said. “We are freeing Mauna Kea with our prayers. Sovereignty is real here. To come here is to take our concerns to a higher authority. “This whole place for me is like a city of refuge. Hawai‘i has offered me sanctuary, given me the ways and means to exercise my heart, given me hope for humanity with kindness. With all Hawaiians have been through, they still have kindness in their hearts and that is what gives me hope. When I think on these things, water comes to my eyes – and I have not done that since I was very small.”